Gustave Doré (1833-1883) and Jean-Charles Davillier (1923-1883) made a long trip to Spain in 1862. Davillier was already a deep connoisseur of our country when, in conversations with the well-known illustrator, he offered to ask him as a guide and insists that he get to know Spain and represent it: he had insisted “more than 100 times that he was the painter who should make Spain known to us. Not that Spain of operetta and keepssakes, but the real Spain… ”(Rodrigo, 1983) situation that would end up taking place, turning Doré’s drawings into one of the obligatory references of everyday Spanish life in the 19th century. Gustave Doré already had a deep interest in the realization of this trip, so the coincidence of interests seemed clear.

The authors periodically sent their impressions of the trip and the illustrations to the travel magazine Le Tour du Munde who would publish them periodically from 1862 to 1873. The following year, all these articles were published by the Bachette publishing house in a book that would quickly reach a remarkable success, being translated into several languages in a few months.

One of the chapters of this work (the XIX) is dedicated to Holy Week in Seville. We will be addressing in other articles the vision and feelings that Holy Week produced to other foreign travelers in our country. An external vision that can give us, on the one hand, valuable information about how the Holy Week celebrations were in the past. On the other hand, it gives us the impressions that these celebrations left on these external observers, which can also provide us with interesting information on the perceptions and feelings that these celebrations left on them and an interesting assessment, from a vision far from immediacy. In the aforementioned article by Doré and Davillier we find a detailed description of the different acts, functions as they say that the Sevillians themselves call them, based on direct observation of them.

The story tells us that the celebrations begin on Palm Sunday with the blessing in the morning of the palms, referring to the different ways in which they are woven and the custom, maintained in our country, even in large cities until no too long ago, to keep them on balconies throughout the year due to the widespread belief that “they have the virtue of preserving houses from lightning” (Doré and Davillier, 1998, p. 448). A protection against this atmospheric phenomenon, which has aroused so much fear in the popular mentality, and for which some magical remedies have been applied such as the fire brands that were placed in some towns around Paris, as the author himself refers in the article, or the well-known lightning stones (polished stone axes) used by shepherds in different places of our geography. The placement of these blessed palms has been considered as an element of general protection in the houses, which is why they were kept all year round on the outside (window or balcony of the same) throughout the year.

In the afternoon of that same day, different processions with steps take place, giving us some information about the route: Calle de los Sierpes, Plaza de la Constitución and Calle Génova to enter the Cathedral through the door of San Miguel, crossing it to exit by the opposite end and go from here, to their places of origin.

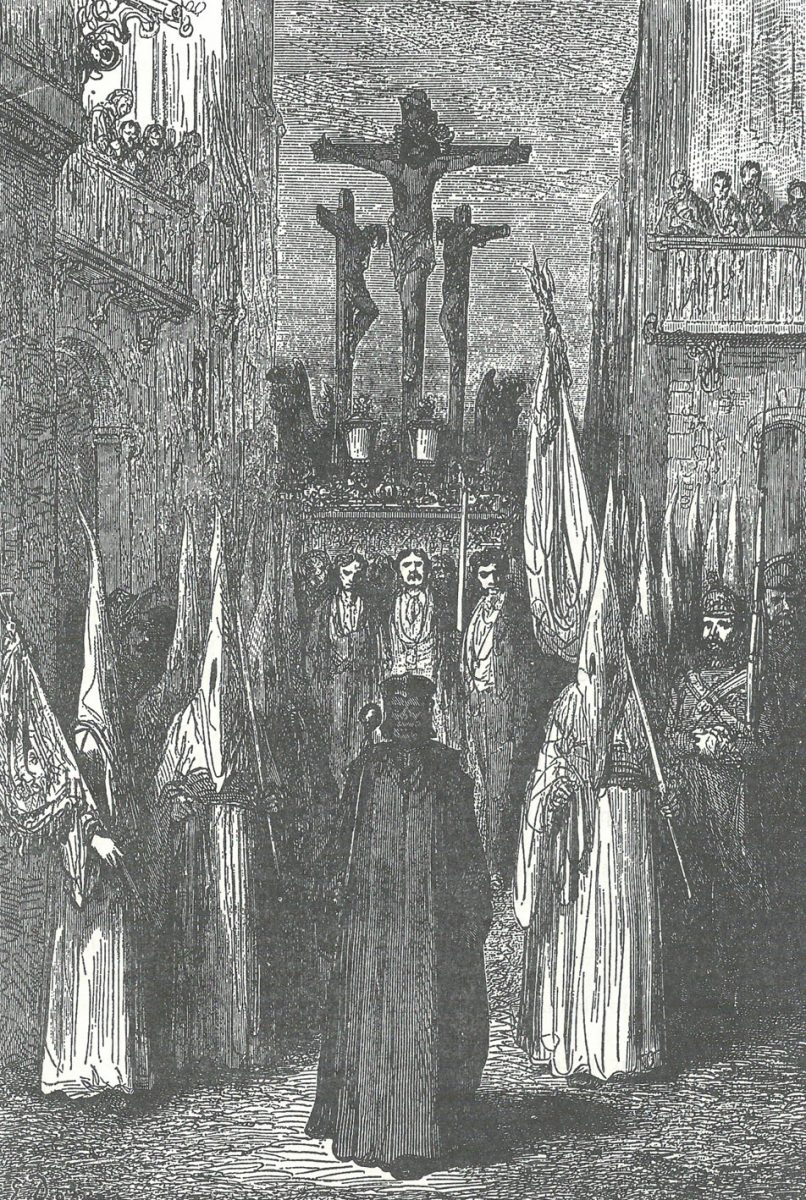

COFRADES ACCOMPANYING A STEP. ILLUSTRATION BY GUSTAVO DORÉ. TAKEN FROM DORÉ AND DAVILLIER, 1998, P. 457.

In this procession he describes the order of one of the steps, the one that went to the head, that of the Conversión del Buen Ladrón: at the head of the procession are some soldiers in full dress, then the blags of the brotherhood and then ” in two rows, a number of characters who played an important role in religious processions and who are called Nazarenes. This name undoubtedly comes from the fact that the penitents in the past wore, remembering Jesus of Nazareth, long hair and a heavy cross on their back ”(Doré and Davillier, 1998, p. 450). In the middle of the procession the Elder Brothers. After the penitents came “the muñidores with long silver trumpets, adorned with rich silk cloths and great luxury of embroidery, fringes and tassels ”. Behind the older brothers are the mozos del cordel, who carry baskets with candles.

On Wednesday the Canto de la Pasión takes place in the Cathedral, with numerous theatrical effects; footsteps go back through the streets. At nightfall the office of Darkness is celebrated in the same temple and later the song of the miserere.

On Holy Thursday morning, the oil paintings are consecrated in the Cathedral and the Blessed Sacrament is transferred to the Monument, which is possibly the same one that was used until the 50s of the last century and which was made by Antonio Florentín in 1545.

Good Friday is “the most solemn day” and in which more brotherhoods participate in the processions. The authors draw attention to the passage of the Santo Entierro, which instead of carvings carries characters of flesh and blood, among which the death with his inseparable scythe stands out and in which there also appear characters of angels, San Miguel, the Santo Ángel de la Guarda and many other characters. An image that recalls medieval theatrical cars and that we can still see in processions in lagoons today.

On Holy Saturday they refer to the procession of the Establecimiento of the Church in which the church is represented by a girl dressed as a priest. Easter Sunday is a festive date with “all kinds of shows” (Doré and Davillier, 1998, p. 454) including the bullfight.

They also make different allusions to the thrones. He makes a special reference to the artistic value of them and to how the most renowned sculptors had worked on these works. The call of attention to how some colors are used in a specific way in the dresses of some characters is significant: blue for the Virgin, Judas Iscariote in blue and white or San Juan with green clothes. The thrones are, as now, mounted on a “platform from which a gualtrapa hangs down to the ground that hides the men below bearing the load. As they cannot see what is happening outside, one of the members of the brotherhood warns them by knocking when they must stop… ”(Doré and Davillier, 1998, p. 451); a procedure the same as that still used.

“The processions of Seville, with their many masked penitents covered with cogullas, offer a strange, almost gloomy spectacle; it is like a remnant of the autos-da-fé of the Inquisition ”(Doré and Davillier, 1998, p. 454). The work of Doré and Davillier is a testimony that allows us to discover the Holy Week of the 19th century and the impressions that they provoke on foreigners. Undoubtedly an interesting document to expand our knowledge of these celebrations and the perception that, from other environments, is had of it.

LEGEND GIVES PHOTO ABOVE:

A THRONE IN SEVILLA: JESÚS NAZARENO DEL GRAN PODER. ILLUSTRATION BY GUSTAVO DORÉ. TAKEN FROM DORÉ AND DAVILLIER, 1998, p. 457.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

EL MONUMENTO AL SANTÍSIMO DE LA CATEDRAL EN HTTPS://WWW.PATRIMONIODESEVILLA.ES/EL-MONUMENTO-AL-SANTISIMO-DE-LA-CATEDRAL (CONSULTADO EL 16/05/2020).

DORÉ, G.; DAVILLIER, J.C. (1874). (1998) VIAJE POR ESPAÑA. 2 TOMOS. MADRID. MIRAGUANO S.A. EDICIONES.

MORALES, A. (1993) “UN DIBUJO DEL MONUMENTO DE LA CATEDRAL DE SEVILLA POR LUCAS VALDES”; LABORATORIO DE ARTE DEL DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA DEL ARTE, 6, PP. 157- 167.

RODRIGO, A. “DAVILLIER Y DORÉ, POR LOS CAMINOS DE ESPAÑA” EN EL PAIS 05/09/1983. EN HTTPS://ELPAIS.COM/DIARIO/1983/09/05/CULTURA/431560803_850215.HTML (CONSULTADO EL 16/05/2020).

SAZATONIL, L. (2011) “EL VARÓN DAVILLIER: HISPANISTA, ANTICUARIO Y VIAJERO POR ESPAÑA” EN CABAÑAS ET AL. EL ARTE Y EL VIAJE. MADRID, C.S.I.C.